As featured in The Spectator, Abortion and the Deep South, 14 September 2018.

In one of the many forgotten decisive moments in the history of the USA the question of the expansion of slavery was being debated. The one in favour of expansion asked why if he could take his animals anywhere then why not his slave? The one against — Abraham Lincoln — argued that this denied the “humanity” of the slave and was contrary to “human sympathies” and the principles of democratic government.

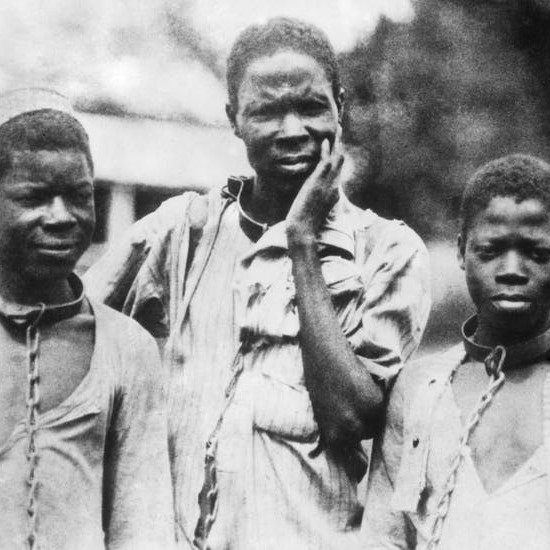

The primary difficulties in that time were that many people were scared about four million former slaves entering the job market and that technology having made slavery more profitable, their ‘owners’ now said it was ‘right’. As well, a subjectivist philosophy had infected the political class and they taught that the fate of the slave was a matter of ‘popular sovereignty’ and that a free people could be ‘indifferent’ about whether a slave was human or was not.

Those opposed to slavery realised that this subjectivist philosophy which denies that our senses provide objective knowledge of the material world was the real difficulty. Democratic life is based on the obvious fact that all men and women are created equal, the necessary political conclusion being that no human being should rule over others without their consent. Yet if the class of human beings was merely subjective no one was safe; if people with darker skin could be made slaves, any of us with our personal characteristics at any time, could be denied our democratic rights. Lincoln’s generation defeated subjectivism by insisting on our common humanity and the dignity of human work, what they called “free labour”. Importantly they defended its accompaniment, the right to strike.

That generation did not bring slavery to the USA, it was a fact of life. Their approach looked to the principle inherent in democratic life and asked what policy would advance it in their situation? Importantly, in asking this question they did not merely mechanically insist on the principle as policy.

The Queensland Parliament’s desire to ‘modernise’ abortion laws has resulted in draft laws which provide scant regulation of the practice based on a principle that abortion is no matter for any public concern at all. The draft law mirrors Victorian legislation, that State being Australia’s ‘Deep South’, a place where human life is cheap and industrial development is scorned and the same subjectivist nonsense of 160 years ago rules the political class.

The anti-slavery argument was not only that there is a difference between a human being and a thing or an animal but that we human beings can’t help but know of this difference. Human reason enables us to understand the substance of everything; be it object, animal or human. This means we can speak of the different things and ask what is just or unjust in our dealings with them. The object we can discard; the animal we are required to deal with more respect even humanely; but human beings we must respect, and their destruction must be aligned in some way with the self-defence of ourselves or the polity.

There is then, a democratic interest against the promotion of a principle that a human life can be disposed of without any public interest or legal limitation at all. This is not to say that abortion is always wrong; but that the Queensland’s Parliament’s adoption of a principle that it is no matter for any public concern at all is wrong. The political division is really between those who believe that in some situations abortion would be wrong and those who insist that no abortion is ever wrong.

The doctor–patient relationship is however not an ethically free zone, nor is a doctor the mere slave of the shifting desires of the patient. The people through the laws made by our representatives have a proper role in guiding the understanding of both doctor and patient about appropriate medical care.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the decision to seek an abortion is a serious and fraught one for most women who do so. That it is so reflects the truth that it involves the end of a human life, a life that might echo in descendants until the end of time. It’s simply not, as one conservative politician said, “an easy way out”.

The proper question for the Parliament is: How can we fashion a law that reflects that element of seriousness encompassing the humanity of the child and the help we can render to a woman in difficulty who has a positive pregnancy test, while at the same time not involving ourselves in every single decision about the continuation of a pregnancy?

To do so we need discard the other claim that this decision should be solely reserved to one sex. It takes both sexes to make the child and too often it is female children who selected for abortion. The right to abortion can’t be peculiar to that sex if that sex is also the victim. Any ‘right to choose’ would arise at the moment of clear sexual differentiation, at around 8 weeks gestation, its exercise awaiting the birth and development of the child into an adult. That ‘right’ would obviously be lost if the child is not allowed to develop and be born. The truth here is reflected in other anecdotal evidence that many women who have abortions say they would not have done so if they had the support of their partner.

The current law mandates consultation with a medical practitioner and the conclusion of harm to the woman carrying the child before the child can be removed. It provides the proper direction to both of them and the man involved, and reinforces the principle of our common humanity so essential to democratic life while keeping the matter properly private. What we need is not a change of law but a change of heart and mind.

Martin Hanson is a Queensland lawyer and a member of the ALP.